The Doomsday Clock, also sometimes called the Clock of the Final Judgment, became not only the Bulletin ‘s emblem, appearing on all its covers, but also an icon of popular culture that has inspired songs, books, films, comics and video games. According to the Bulletin ‘s current president and CEO, Rachel Bronson, Martyl proposed this idea “both because of the urgency that it conveyed and also because of the tick, tick, tick, tick nature of it-that it would move toward midnight unless we could push it the other way.”

She was the author of the clock’s visual metaphor: set against an attention-grabbing bright orange background, the black-and-white hands placed at seven minutes to midnight suggested a countdown to the annihilation of humanity by nuclear war. Its cover illustration was commissioned from artist and Bulletin member Martyl Langsdorf, also the wife of Manhattan Project physicist Alexander Langsdorf. In 1947, what had begun as a mimeographed pamphlet was transformed into a printed magazine, with the aim of reaching a wider audience. Robert Oppenheimer, Max Born, Hans Bethe and Edward Teller, among others. Alongside its founders, Eugene Rabinowitch and Hyman Goldsmith, the Bulletin brought together a large group of contributors including Einstein and Szilard, along with names such as J. In the month following the bombings in Japan, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists of Chicago was established to “equip the public, policymakers and scientists with the information needed to reduce man-made threats to our existence.” This goal was embodied in the publication of a newsletter that compiled articles by leading scientists and academics. The historical fluctuations of the most famous minute hand Einstein, who did not work on the project, also regretted signing the famous letter. The scientists involved were well aware of the ultimate purpose of their work, although many of them opposed its use against civilians and were horrified by the consequences. And although Roosevelt’s reaction was not immediate, it was the first step towards what in 1942 would take shape as the Manhattan Project, which in turn led to the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, ending the global war. That letter has been called one of the documents that changed the world, and not surprisingly one month later, World War II broke out. The letter concluded by suggesting that the government of Nazi Germany might already be exploring this avenue. It was the German physicist who on 2 August 1939 signed a letter -actually penned by his colleague Leo Szilard-to the then US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, drawing his attention to the possibility of using a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium to build “extremely powerful bombs of a new type”.

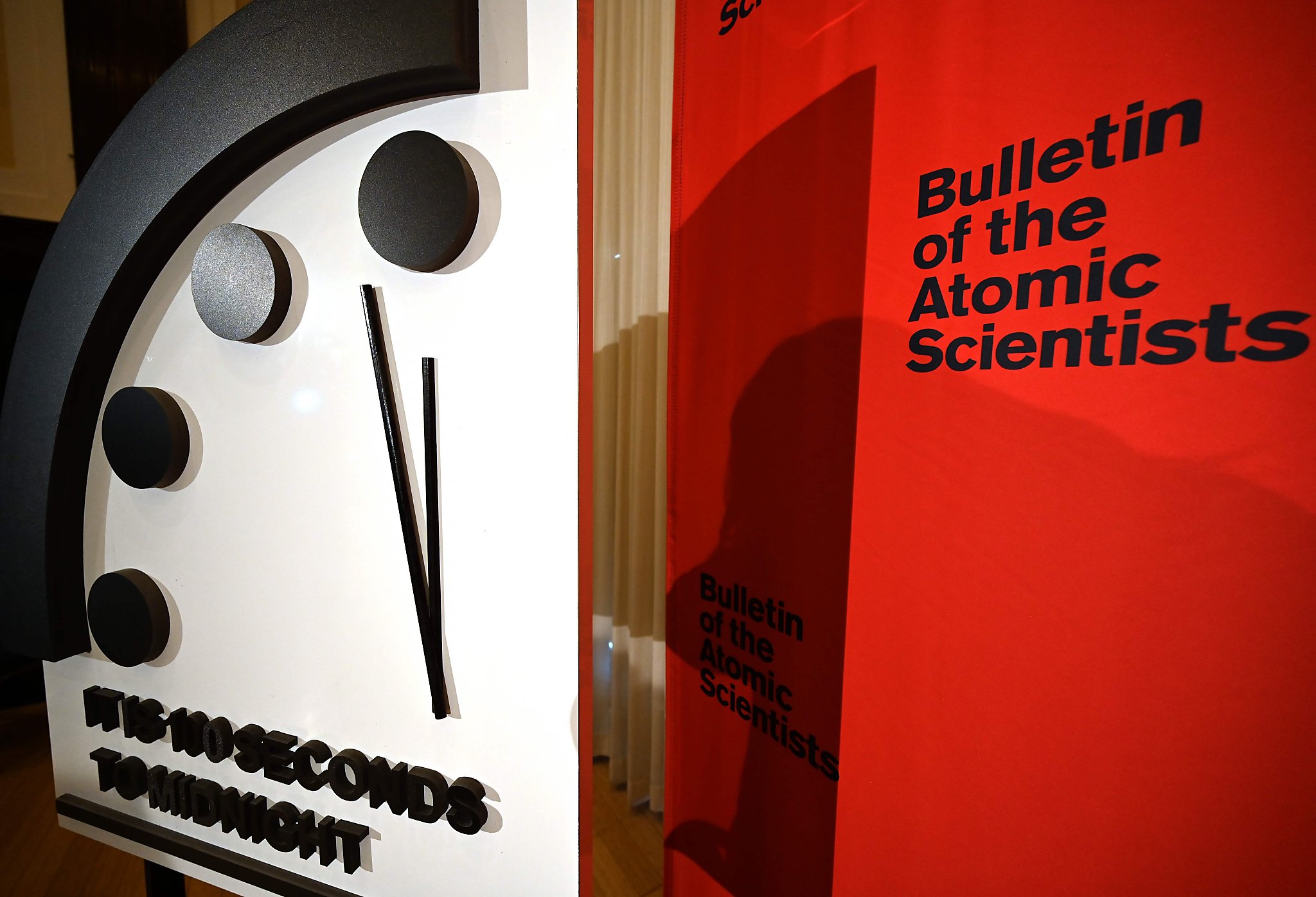

The Bulletin proudly bears its origins, in which the name of Albert Einstein figures prominently. Source: Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Original cover of the first edition of the Doomsday Clock (right) compared to the 1958 edition (left). Since 2020, the clock has been set at only 100 seconds to midnight, the closest it has ever been to the end in its entire history.

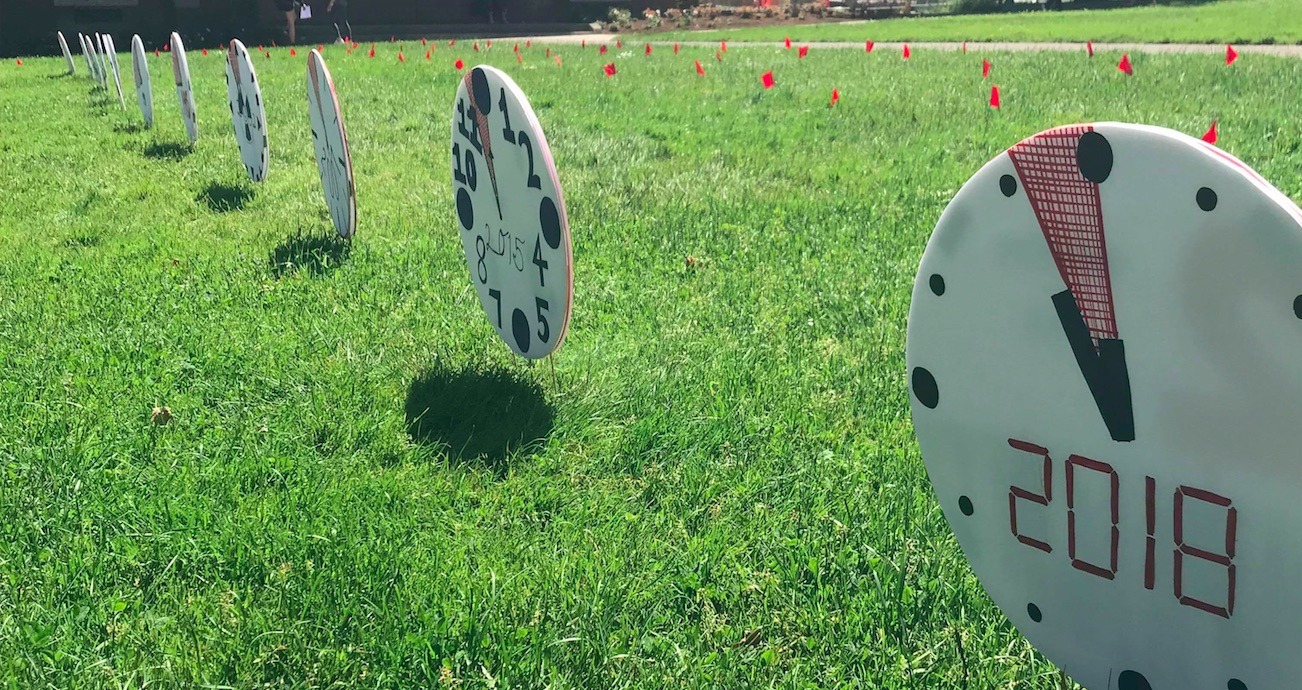

Since then, the so-called Doomsday Clock has served as a warning and reminder of the global existential threats created by humanity against itself, which today also include climate change and more, while its hands have been moved forward or backward depending on the intensity of the risk. That first issue had a simple image on its cover, a clock with its hands set at seven minutes to twelve, with which the Bulletin ‘s members wanted to warn of how close humanity was to annihilation-midnight-due to the danger of nuclear war. In June 1947, what had previously been a newsletter published by a group of scientists from the former Manhattan Project at the University of Chicago became a full-fledged magazine with the title Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)